Definition

Loss of hair attributable either to the effects of inflammatory cells on follicles or to physiological or mechanical factors in which inflammatory cells play no role. Although the scalp is the site most often affected, any region of the skin that bears hair follicles may be involved by certain types of alopecia

Course

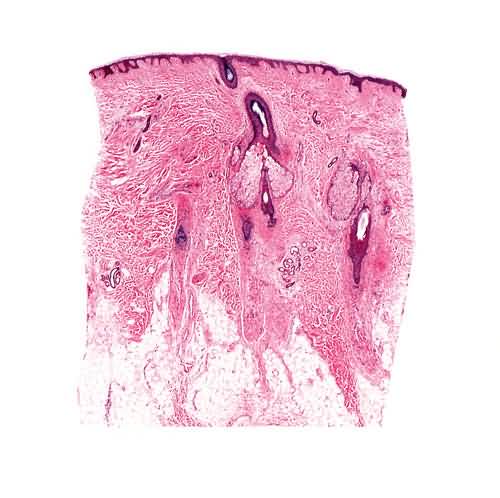

Both basic types of alopecia, namely, those unassociated with infiltrates of inflammatory cells (e.g., common baldness and telogen effluvium) and those associated with infiltrates of inflammatory cells (e.g., lichen planus and lupus erythematosus; see also the chapters on lichen planus and lupus erythematosus, respectively), display a characteristic sequence of clinical and histopathologic changes. In the case of common baldness, for example, the loss of hair at the outset is hardly noticeable, but after years a man may be nearly entirely bald. During this time, the follicular cycle (growing, involuting, and resting stages) shortens progressively so that each cycle becomes shorter than the last and each follicle becomes progressively thinner and situated higher in the subcutaneous fat and, in time, within the dermis. Eventually, the long terminal follicles with their long sturdy hairs are converted into short vellus follicles with their short wisp-like hairs.

In the case of lichen planus, for example, changes at the outset in the skin and in hairs are hardly noticeable clinically, but eventually reddish violet plaques become progressively alopecic and, still later, all that is left are white patches, some of them scarred, of alopecia. The dense lichenoid infiltrates of lymphocytes that surround follicles of lichen planopilaris at a relatively early stage of the process are responsible for destruction of follicular epithelium and for induction of alopecia by the effects of fibrotic tracks that eventually replace the follicles. Traction alopecia simulates closely lichen planopilaris histopathologically but findings at all stages enable differentiation of them, e.g., wedge shaped hypergranulosis and orthokeratosis in lichen planopilaris during the ” active” stage of it and fibrous tracks widened markedly by thick bundles of collagen in traction alopecia at the end stage of it.

In common baldness and lichen planus, despite the fact that the former is a non-inflammatory process and the latter is an inflammatory one, the result is the same, namely, permanent loss of hair. In the case of common baldness, effete follicles are still present and there are no signs of scarring, either clinically or histopathologically. In lichen planus, however, no follicles remain at sites of alopecia; they have been destroyed, and there are signs of scarring at sites where formerly there were follicles.

A predictable sequence of events can be anticipated in non-inflammatory alopecias, like so-called telogen effluvium, and in inflammatory ones, like discoid lupus erythematosus. In the former, hairs always return, whereas in the latter, they do not. It is impossible to predict accurately the course of alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis. As a rule, the longer the failure of hairs to regrow, the less likely will be their return, even should treatment eventually be instituted for that purpose. In the absence of any therapy, some patients with these three variants of a single distinctive type of inflammatory alopecia show signs of reappearance of hairs within weeks, others in months, and still others never. If therapy in alopecia areata and its more extensive equivalents is going to be effective, some evidence of regrowth of hair should bAlopecia Totalis and Alopecia Universalis Alopecia areata is characterized by nonscarring hair loss of unknown etiology. Manifestations are most frequently limited to a few oval bald patches. However, a minority of individuals develops extensive areas of hair loss or even loss of all body hair (alopecia totalis or universalis). The pathogenesis of alopecia areata is poorly understood; however, biopsy of active lesions demonstrates peribulbar lymphocytic infiltration and therapy is intended to suppress this inflammation.

First steps Limited hair loss

1. The initial strategy may be no treatment as regrowth, particularly in paucilesional first episode alopecia areata, is common in 2-6 months.

2. If treatment is instituted, eradication of inflammation by topical application or intralesional injection of corticosteroids is of value. Topical clobetasol 0.05% in a cream vehicle applied to the bald patch twice daily with assessment of response in 4-6 weeks. If intralesional injection is selected, use triamcinolone 2.5-10 mg per cc, and if necessary repeat treatment every 4-6 weeks until response is complete.

Extensive hair loss

1. A reliable, standard, low risk therapy is not available.

2. Intralesional corticosteroid injections are not practical for patients with alopecia totalis, but may be used in this setting to induce hair growth in cosmetically important areas such as the eyebrows.

Alternative steps

Limited or extensive hair loss

Multiple modalities have been described, but none is clearly superior.

1. Application of minoxidil 2%-5% or 3% every day or 2 times daily may be attempted.

2. Anthralin-induced irritant dermatitis is safe and may be beneficial. Application of anthralin 0.25%-1.0% in petrolatum or paste to the scalp for 20-30 minutes nightly at bedtime to induce an irritant dermatitis. Continue the therapeutic trial for 2-4 months.

3. Contact allergen application may be efficacious. Diphencyprone may be used, sensitizing at 2% on a 4 cm diameter spot on the inner arm and starting applications to the scalp at 0.0001% with gradual escalation to induce slight reaction (mild erythema and pruritus lasting about 36 hours). Squaric acid dibutyl ester, another potent topical allergen, may be used. Sensitize with a 2% solution in acetone, and elicit dermatitis with a 0.2-0.4% % solution in acetone

Pitfalls

1. Corticosteroid injections may cause focal reversible scalp depressions, and has been rarely reported to cause blindness if injecting around the eyes.

2. Systemic steroids induce hair growth in patients with extensive alopecia areata, but such therapy is not recommended. High doses are usually required, and hair loss recurs after steroid discontinuation. The complications of long-term high-dose steroid therapy are not justified.

3. Alopecia areata is associated with other autoimmune disorders, including thyroid disease, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and Addison’s disease.

4. Contact immunotherapy may result in widespread dermatitis and lymphadenopathy.

5. Anthralin therapy may cause cutaneous staining.

6. In severe cases, stopping immunotherapy or other treatments is often associated with return of the alopecia, so maintenance therapy is required.

ecome apparent in weeks. In many persons afflicted, however, therapy is ineffective.