Definition

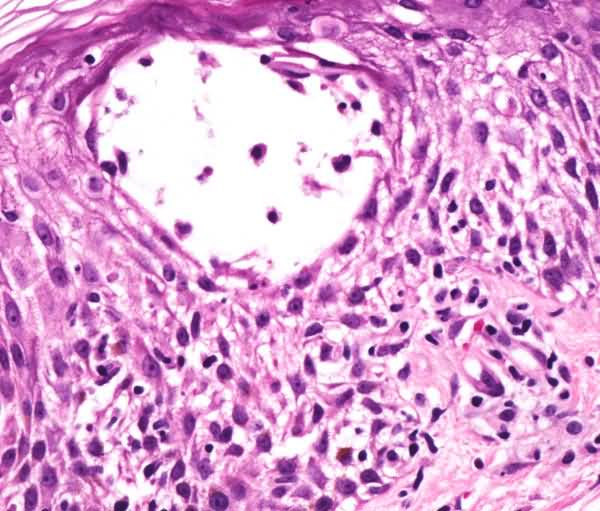

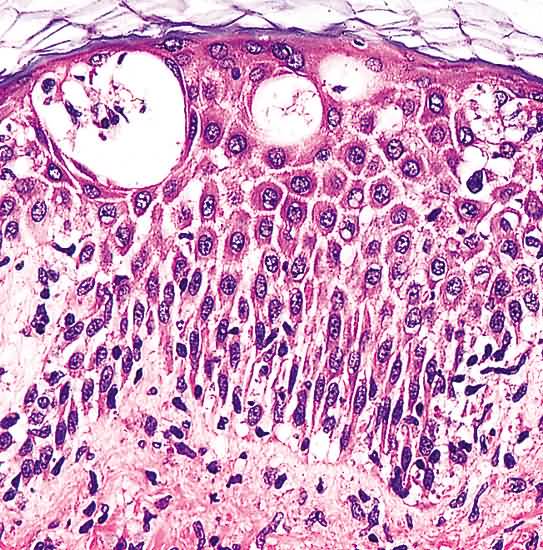

Allergic contact dermatitis is an inflammatory process induced by direct contact of the skin of a sensitized individual to an allergen. Within hours, red macules or patches develop that usually evolve rapidly, sometimes through an intermediate stage of urticarial papules or plaques, into vesicles that may become bullae. Because the lesions, i.e., macules, papules, vesicles, and bullae, are not in themselves specific, diagnosis clinically is made by virtue of distinctive distribution that reflects the manner in which a particular allergen was contacted. Examples of common allergic contactants are Rhus toxicodendron (“poison ivy”), nickel, thiurames in rubber, parabens in ointments, and chemicals in fragrances, whereas agents commonly responsible for irritant contact dermatitis are acids, alkaloids, machine oils, organic solvents, and oxidants.

Course

Within hours after the skin of a sensitized person has come into contact with a particular allergen, red macules or patches develop that usually evolve rapidly, sometimes through an intermediate stage of urticarial papules or plaques, into vesicles that may become bullae. Sometimes, however, allergic contact dermatitis may present itself only as reddish papules or papulovesicles, but more often as tense vesicles as well. Episodically, depending on the patient’s degree of hypersensitivity, bullae may come into being. If the offending agent is removed, lesions of allergic contact dermatitis, no matter how widespread or severe, resolve, even without therapy, in a matter of weeks at most. If, however, the allergen continues to come into contact with the skin, the process may persist for years. In that latter situation, annoying pruritus leads to persistent rubbing, which causes lichen simplex chronicus to be imposed on the effects of longstanding allergic contact dermatitis.

The same general principles that apply to allergic contact dermatitis apply equally to irritant contact dermatitis, the earliest stage being red macules or patches that very soon are surmounted by vesicles or bullae, or both. In the case of irritant-induced blisters, however, the roof of the lesions often has a gray cast, a consequence of the epidermis having become necrotic secondary to the effects of the irritant. Although both allergic contact dermatitis and irritant contact dermatitis result from direct contact of the skin with an offending agent, the two mechanisms are completely different; allergic contact dermatitis results from immunologic mechanisms, whereas irritant contact dermatitis does not.

Overview

Contact dermatitis can have either an irritant or an allergic origin. Irritant reactions tend to appear less than 12 hours after exposure and are strictly limited to exposed sites. Allergic reactions are delayed (12 to 72 hours, except for primary sensitization, where an induction phase of 7 to 10 days is typical), and exhibit a tendency to spread as the delayed hypersensitivity reaction reaches sites where less antigen was deposited initially. Since the clinical manifestations result from the cutaneous inflammatory reaction caused by contact with an exogenous chemical agent, the therapeutic strategy is to eliminate the inciting agent and to suppress the inflammatory reaction. Irritant contact dermatitis is managed by keeping the skin moist and protecting it from further irritant exposure. Topical steroid therapy during the first week may be beneficial. The discussion below refers to the management of allergic contact dermatitis.

First Steps Limited Areas of Involvement

1. If the lesions are bullous or weepy, treat with cool compresses, using Domeboro tablets or packets, one tablet or packet in 1 pint of tap water. A clean washcloth or towel should be used and applied wet (but not soaking wet) to the rash for 15 to 20 minutes twice daily.

2. Prescribe a superpotent or high potency topical steroid preparation in a drying vehicle (e.g., gel or cream but not ointment) to be applied twice daily to the rash. Note: For acute contact dermatitis on the face or intertriginous areas, milder topical steroid (e.g., desonide, aclomethasone) or hydrocortisone 2.5% cream is preferable.

3. For additional relief of pruritus, an astringent lotion, with or without additional ingredients such as menthol, camphor, and phenol in low concentration (less than or equal to l%), can be applied as frequently as needed.

4. If pruritus is interfering with sleep, low doses of antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine) can be prescribed.

Widespread Involvement

1. Systemic steroids: Topical steroids are only minimally effective for: widespread (>30% body surface area) acute contact dermatitis. Therefore, as disease becomes more generalized and/or involves face, genitalia, or other areas that compromise normal activity, a course of systemic steroids may be indicated. For reexposure (as in recurrent episodes of poison ivy or poison oak), a 10- to 14-day tapering course of prednisone, beginning with 50 or 60 mg/day, is indicated. Administer each day’s medication as a single morning dose taken with food or a glass of milk to reduce the likelihood of stomach upset and to avoid steroid induced insomnia.

For patients with primary sensitization (first episode), where the course may extend up to 4 to 6 weeks, oral prednisone beginning at 60 to 80 mg/day in a single morning dose may be used until the dermatitis is under control and obviously receding (usually 72 to 96 hours). Then reduce prednisone as often as every 3 to 4 days in 10-mg steps, being sure to treat the patient for at least 3 weeks from the onset of the eruption before discontinuing systemic steroids.

Alternatively, a single intramuscular injection of triamcinolone acetonide 40 to 60 mg total, together with an additional 1 cc of betamethasone valerate, will provide a fairly rapid onset of action and prolonged action over 2 to 4 weeks. Note: Intramuscular steroids should be administered deeply intramuscularly in the buttocks to avoid possible atrophy of overlying subcutaneous fat.

As a further precaution, in all patients who are candidates for systemic steroids, ascertain the presence or absence of absolute or relative contraindications to steroid therapy (e.g., brittle diabetes mellitus, active tuberculosis or other chronic bacterial or fungal infection, poorly controlled glaucoma, or psychiatric disease). In patients with HIV infection and other forms of immunosuppression, the risk benefit ratio for prednisone therapy should be determined on a case by case basis. Note: Women should be warned that these doses of systemic corticosteroids can cause short-term menstrual irregularities.

2. Cool baths with oilated colloidal oatmeal can provide temporary relief for patients with extensive disease.

3. Secondary bacterial infection, although uncommon, may occur, and can be hard to detect in extensive contact dermatitis. Administer oral systemic antibiotics, such as dicloxacillin or cephalexin 1 g/day to patients with obvious infections.

Subsequent Steps

1. Because allergic contact dermatitis, particularly to plant lipid soluble antigens (poison oak or poison ivy) may be a 4 to 6 week illness, short courses of systemic steroids may result in recurrence. Be prepared to treat for the entire duration of the allergic reaction. 2. Airborne contact dermatitis can be difficult to distinguish from photoallergy or phototoxicity. In airborne contact dermatitis the reaction is concentrated in folds of the face and neck (eyelids and neck) whereas these areas are relatively spared in photoreactions.

Therapy

1. Because allergic contact dermatitis, particularly to plant lipid soluble antigens (poison oak or poison ivy) may be a 4 to 6 week illness, short courses of systemic steroids may result in recurrence. Be prepared to treat for the entire duration of the allergic reaction. 2. Airborne contact dermatitis can be difficult to distinguish from photoallergy or phototoxicity. In airborne contact dermatitis the reaction is concentrated in folds of the face and neck (eyelids and neck) whereas these areas are relatively spared in photoreactions.